Two exceptional exhibitions in Berlin show how relevant the Norwegian modernist painter is today. I spoke with one of the curators, Trine Otte Bak Nielsen

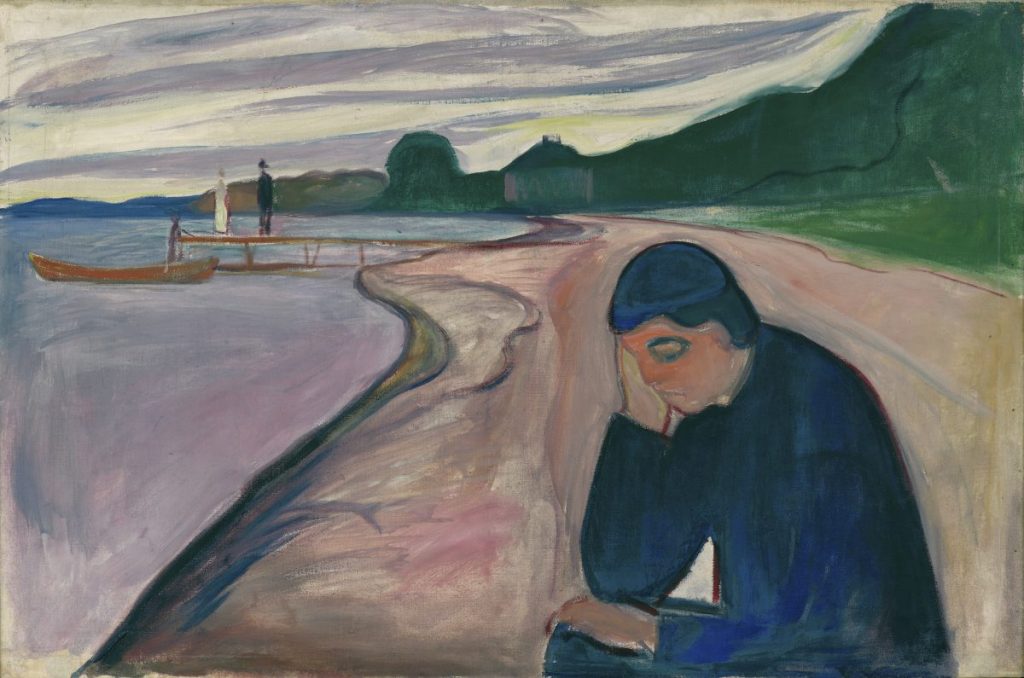

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) is considered one of the most important modern artists. His colorful, psychologically dense imagery caused a stir at the end of the 19th century. Celebrated by the avant-garde, despised by the salon painters of the time, he became part of the Symbolism movement and pioneer of Expressionism. Early stays and exhibitions in Germany had a great impact on his contemporaries and encouraged an enthusiasm for everything Nordic. Munch’s joy of experimentation and lifelong preoccupation with recurring motifs also make him a pioneer of contemporary art practices. Before his death in 1944, he stated in his will that all pictures in his possession should go to the city of Oslo. These include many late works, landscapes, garden scenes and self-portraits that were created in his studio in Ekely. These pictures in particular, with their loose brushstrokes and bright colors, still look like they were freshly painted today. Now a whole trove of these works are on view in Potsdam’s Museum Barberini in the show Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth. It runs until April 1, 2024. At the same time, the exhibition Edvard Munch: Magic of the North (September 15th – January 21st, 2024) is running in the Berlinische Galerie, also featuring many items on loan from Oslo. Lots of Munch this fall in and around Berlin. And a good reason to talk to Munch expert Trine Otte Bak Nielsen, Senior Curator at MUNCH Museum in Oslo, about what the Norwegian painter still has to say to us today.

What makes Edvard Munch so popular?

He has a directness of expression, something immediate that is easily understood and accessible. Because he didn’t paint in the realistic style of the time, but in his own timeless way, his work has remained fresh and universal. And especially in this new modern building he appears to us as an absolutely modern artist. Many of his paintings do not show at all that they were painted more than 100 years ago. They look as if they were painted today. When I worked with Marlene Dumas on an exhibition here, she was also quite surprised by the freshness and modernity of his work. That’s why it wasn’t so easy to find the right paintings for the collection presentation. We have so many great works. I get goose bumps every time I browse through the archive. We also lend out a lot of pictures for external exhibitions at other museums. And we also keep changing pictures in our permanent exhibition to show lesser-known works.

You are currently curating an exhibition that will be on view at the Museum Barberini in Potsdam in the fall. The title is Trembling Earth. On display will be a lesser-known part of Munch’s oeuvre: forests, gardens, fields, seascapes and beach panoramas – earthy motifs. Isn’t there a danger that Munch fans will be disappointed if the icons are missing?

I don’t think so. People will be more excited about discovering new images and new aspects of his art. We want to show that Munch was not only a portraitist and painter of people, but that nature was a central part of his work, too!. But also for those who love his icons, as a highlight there is the Scream to see, this time as a lithograph. We show it together with the Sun, one of his fantastic large formats that are rarely seen outside Oslo. In fact, there will be several versions of the sun motif on view, all first version for his biggest commission ever, for the University Aula. It will be the first time these paintings will be seen again in Berlin, where Munch exhibited them in 1913. But in the Trembling Earth exhibition there will also be paintings with groups of figures, only this time you will see them more in the context of his nature motifs in which he places them. It’s important not to always think of the scream as just a figure expressing Munch’s own anguish and inner pain. It’s also about the world around it. That’s why Munch is still relevant today. His paintings are ambiguous; you don’t know what exactly you’re looking at unless you read the title first. This openness keeps his work interesting, because it always makes you question things.

Also shown are Munch’s paintings of nude bathers in Warnemünde, which he painted around 1907. You see burly naked men at the beach – a sunny, virile mood. Actually untypical for Munch. How did this series of paintings come about?

There were these artist colonies in Denmark, Sweden and Germany at the turn of the century. Munch knew of Scandinavian artists who joined these colonies, but he himself was never part of them. However, he was interested in the way these groups painted outdoors. In Warnemünde, he rented a house from a local fisherman. He lived there alone, but often traveled to Berlin and had contacts in Lübeck. There is, after all, this myth that Munch was gloomy and plagued by anxiety, and only late in life was able to free himself from it and paint sunnier pictures. The Warnemünde pictures prove the opposite, because they were all painted before his psychological breakdown. They are his most vital motifs ever. He painted outdoors, in the archive we have pictures of him standing naked on the beach, in the middle of this nudist colony, working with naked models. That the pictures were made directly on the beach can also be seen from the fact that there are traces of Warnemünde sand in the layers of paint. You can see that he really experiments with new expressive techniques here, he emphasizes horizontal and vertical lines in some of the motifs. And he also thought a lot about healthy ways of living. In his notes from this period, he writes of sunbathing, oatmeal, and healthy eating.

Without his trips to Germany, Munch probably would not have become the artist he was.

Trine Otte Bak Nielsen

During this time, Munch was also preoccupied with wacky subjects like crystallization, cosmic circles of life, and solar worship. Was he an esoteric mystic?

I would call him more of a pantheist. He had a Christian upbringing. His father was a strict Christian. But Munch never described himself as a Christian. Nevertheless, he dealt with Christian mythology in his symbolist paintings. At the same time, however, he always observed nature very closely and was concerned with natural cycles of life. In his paintings you can see dead bodies on the ground, from which blooming flowers sprout, trees grow. In the painting The Blossom of Pain (Blossom of Pain), one sees a dead body giving life to a flower. In the work The Hurting Artist (Hurted Artist), the artist’s heart is bleeding, a flower sprouts from the blood on the ground. He not only paints this, but lives it. In his writings he talks about how we are all part of nature and that God is in all things – an almost Buddhist thought. It’s actually a very positive worldview. But it was often read differently in his paintings. For example, his motif of The Mountain of Man was read as a negative symbol of human existence. But the full title is Human Mountain Towards the Light. People are all striving toward the light that shines above the mountain. There are different levels of existence, but all strive toward enlightenment.

How important were the stays in Germany for Munch? Could one say that there is also something very German in the great Norwegian artist?

Kristiania, as Oslo was called at the time, was still very small at the end of the 19th century and Norway as a whole was rather provincial. For this reason alone, Munch’s visits to Germany were very formative. Between 1892 and 1908 it was Germany he most often visited and lived for longer periods. He felt very connected to Germany and traveled throughout the country. He spent longer periods in Berlin, several times in Lübeck, Chemnitz and also in Weimar. He was very interested in the German artists of that time. His works were published in the magazines like Die Freie Bühne und Pan. In his notes he also mentions Ernst Heckel. We do not know if the two met, but it is quite possible. He wrote letters in German and spoke the language. Without his trips to Germany, Munch probably would not have become the artist he was.

Is there actually also a critical debate about Munch’s work? I’m thinking primarily of his depiction of women. Images like Vampire or Madonna show women as bloodsucking femme fatales, whores and saints – common stereotypes at the time. But are such depictions still relevant today?

Scientific research has changed a lot since the 1950s: Back then, Munch was still seen as the lonely genius and his work was read very much in the context of his biography. Since few relationships with women were known, this was interpreted as an indication that he was a loner and generally distrusted women. Recent scholarship, on the other hand, focuses more on the work itself and not so much on his biography, although the two are of course connected. This does not necessarily mean, however, that every woman who appears in his paintings and has red hair represents his mistress, Tulla Larsson. That would be too simple. Then Munch would not be as relevant today as he actually is. His depictions of women are very complex. Of course there are stereotypes like the seductress or the jealous man. But he also paints the opposite, very vulnerable people – and with great compassion. Do you know the original title for the vampire motif? Munch called the painting Love and Pain. The title change most likely came about through the Polish writer Stanisław Przybyszewski. Munch exhibited the painting in Berlin in 1893, Przybyszewski wrote about it and brought up the vampire comparison.

In what circles did Munch move at any given time? That was a moment of great social and cultural upheaval. The beginning of modernity. But it was also a time when women had little to say in art.

In Norway, Munch’s painting was not particularly appreciated at first. In Berlin, on the other hand, he found a more open-minded audience around the turn of the century. He joined a circle of literati, artists, and intellectuals, including Swedish playwright August Strindberg, Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland, and German art historian Julius Meier-Graefe. They met at the Gasthaus Zum schwarzen Ferkel Unter den Linden and discussed Nietzsche’s philosophy, psychology and and recent scientific research. People like Przybyszewski and Strindberg could clearly be called misogynists from today’s perspective, but I wouldn’t call Edvard Munch that. In our archives we have loving letters to his aunt, that was a wonderful, respectful relationship. And we know that he had long friendships with women. So I wouldn’t call him misogynistic.

Munch is also a pop cultural phenomenon. He is so popular that he has his own emoji. There’s a great danger that the younger audience in particular will only look for click motifs. First take the selfie with the scream, then buy the matching T-shirt in the store and post it all on Instagram or Tik-Tok. How do you get visitors to engage more deeply?

First of all, by mixing the popular motifs with the not-so-familiar ones and presenting different media: Paintings, sculptures, woodcuts, but also photography and film. The open architecture also helps. People are invited to make their own connections to different works. And there are very many different approaches to Munch, sometimes playfully interactive like in the exhibition about his life, where his house is made walkable, sometimes very focused on a specific aspect of Munch’s oeuvre like his woodcuts, where we make it very clear how he worked.