In this rare interview the iconic Japanese fashion designer strikes an existentialist pose and meets his match in photographer Jerry Berndt

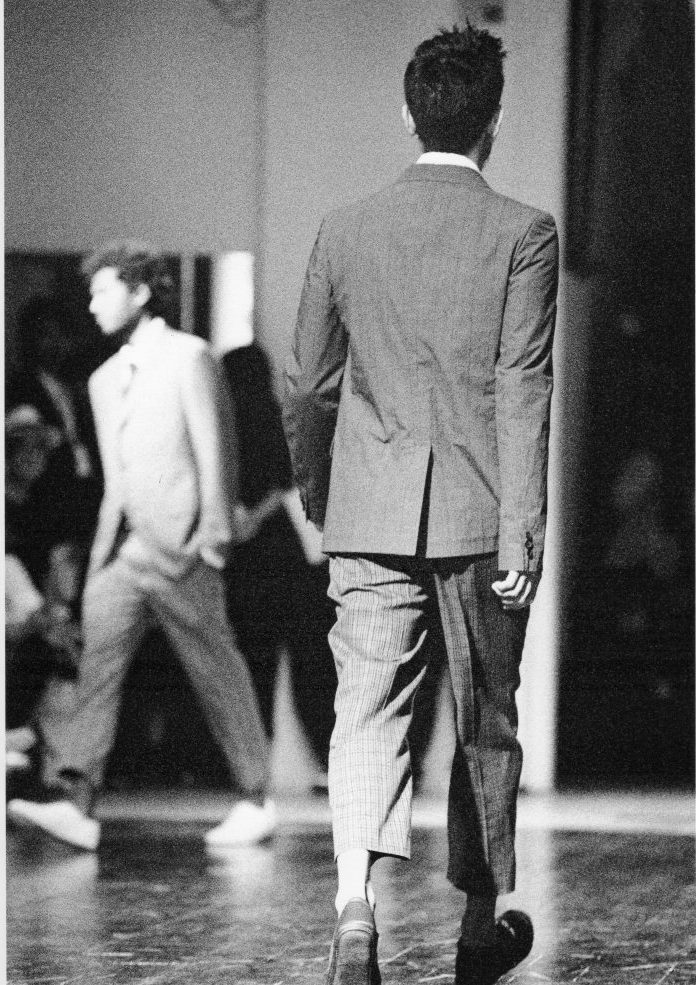

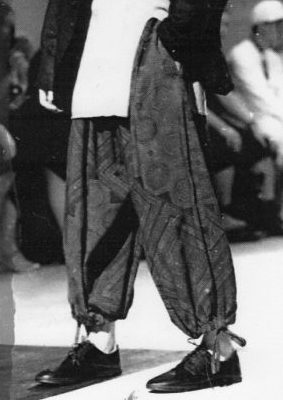

Paris, late June. On Rue Saint Martin, a side street not far from the Centre Pompidou, an exotic crowd gathers in front of a doorway: bald men in golden kaftans, delicate Asian women in severe black dresses and oversized hats, cameras clicking, limousines pulling up. It's Fashion Week, and this evening Yohji Yamamoto is presenting his menswear collection in his Parisian atelier. The models showcase floral harem pants, loose trench coats, asymmetrical shirts, straw hats, and bruises on their faces. After 20 minutes, it's all over. Loud applause. The designer bows with a shy smile. The words "For Sale" are printed on the back of his jacket.

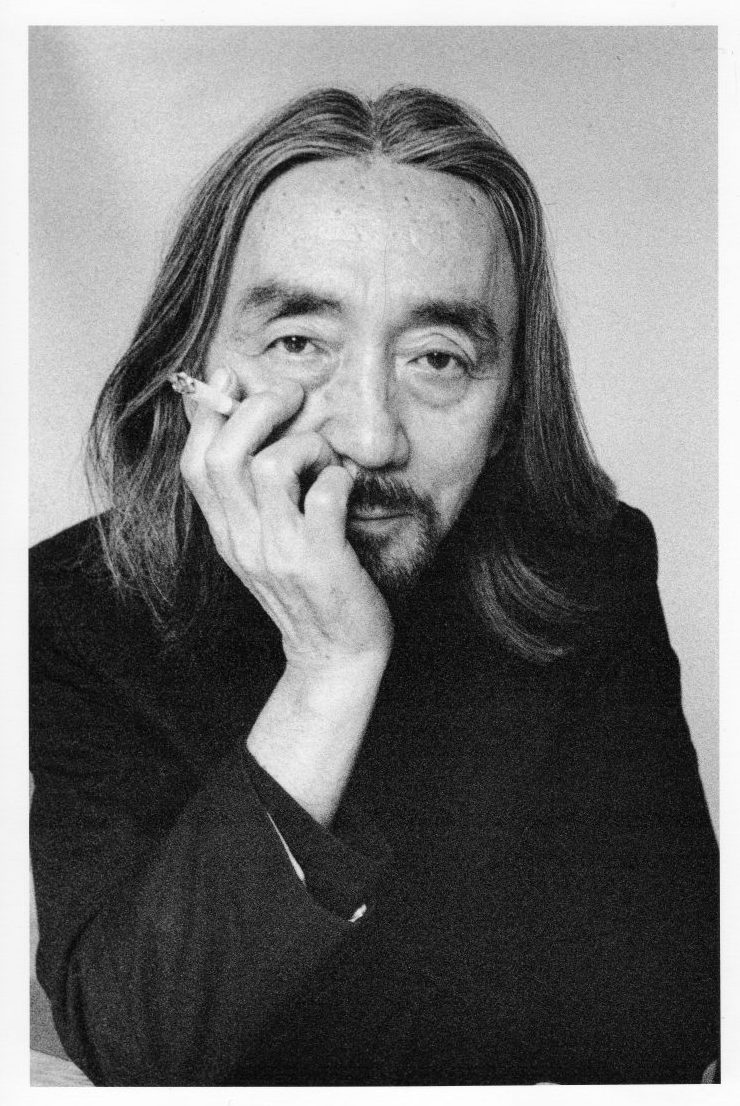

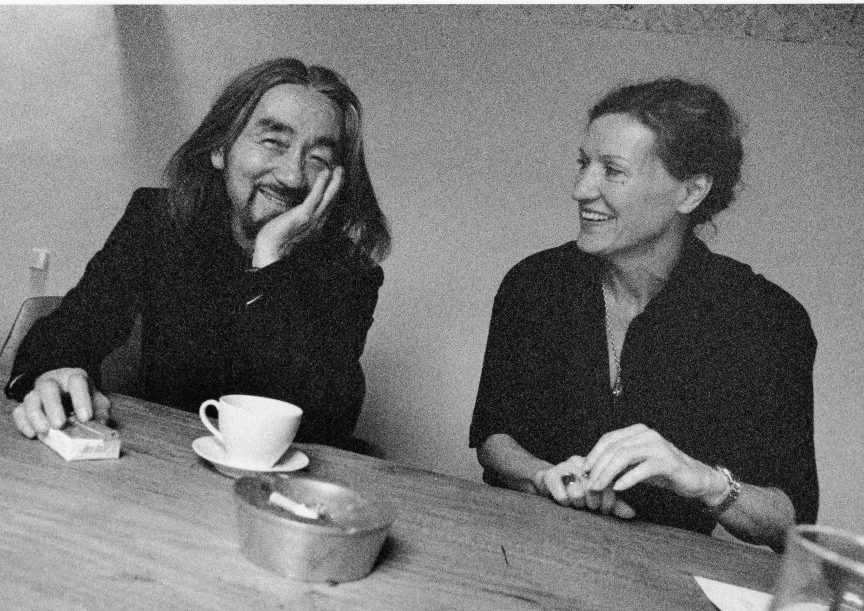

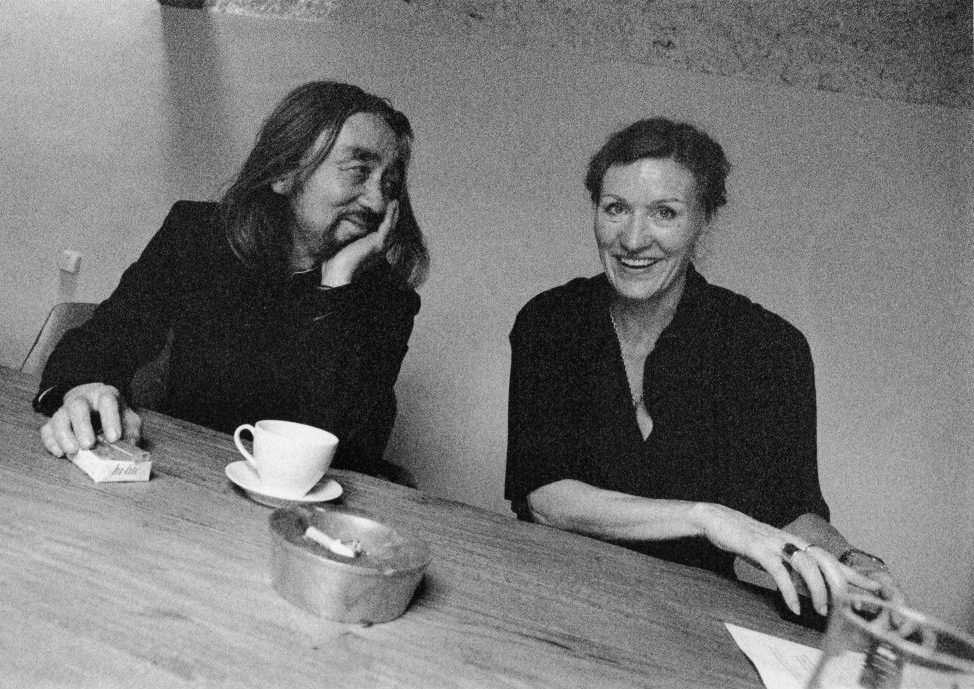

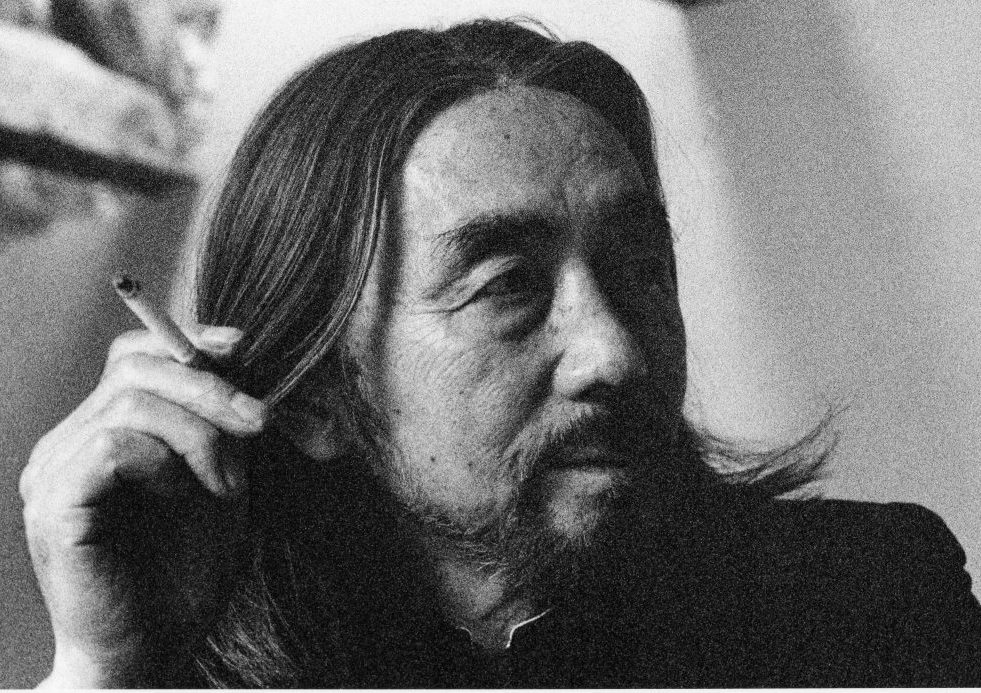

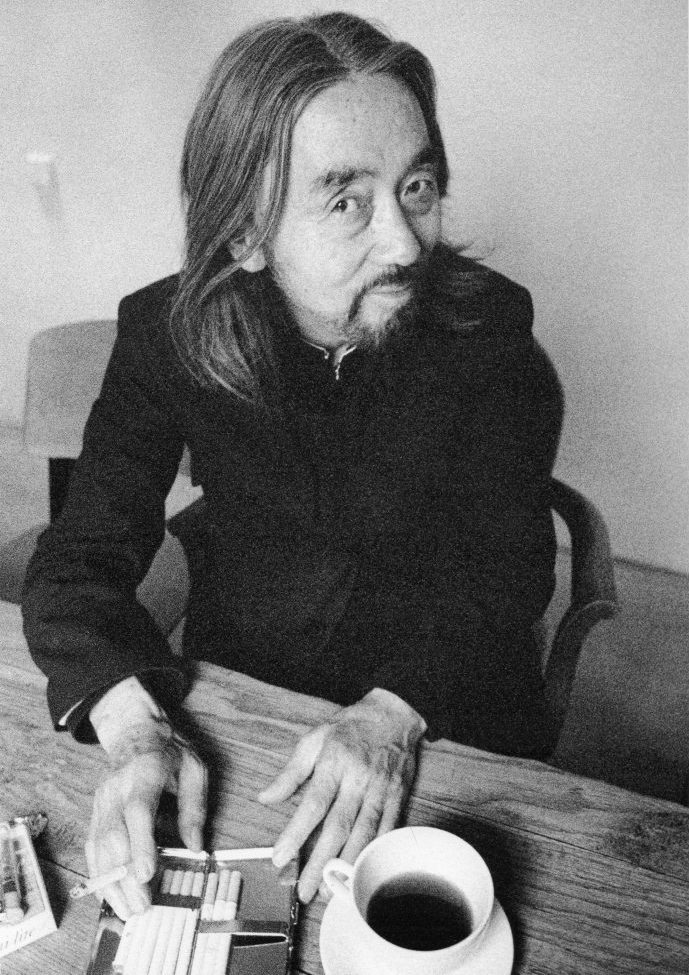

That was thirteen years ago. I met Yohji Yamamoto for an interview in Paris. A special encounter, not least because the Japanese designer has cult status. Yamamoto rarely gives interviews, and when he does, his answers are often monosyllabic, as if he generally doesn't like talking about himself or his work. To break the ice, I brought a friend along: Jerry Berndt, a master of street photography and a legend in his own right. He was to take the portrait photos and coax the shy Japanese man out of his shell. Roughly the same age as Yamamoto, Jerry has documented America's civil protests, the genocide in Rwanda, and Boston's red-light district. He has no interest in fashion. But he plays the harmonica incredibly well and is passionate about jazz and blues—just like Yohji Yamamoto. Jerry's photographic aesthetic is also old-school: black and white, analog, no flash, hand-printed. This insistence on classic craftsmanship—that's something they both share.

The designer greets us with businesslike coolness at the interview appointment. He says he has very little time, and practically none for photos. "Fine with me," Jerry says. "I'll stay in the background and shoot while you're talking." Beforehand, I introduce the photographer. The man behind the camera isn't exactly unknown, I say. His works hang in famous museums like the MoMA in New York. "Hmmm," the designer grumbles. Jerry is also very familiar with the blues scene and has even performed with Muddy Waters. At that, the fashion designer jumps up as if he's been electrocuted. "Muddy Waters??" he exclaims, astonished. When Jerry tells us about his gig with Muddy Waters, an American blues legend, Yamamoto is electrified. He lights a cigarette—one of many during our conversation—laughs, and declares with shining eyes that Muddy Waters is the greatest musician of all time. The ice is broken!

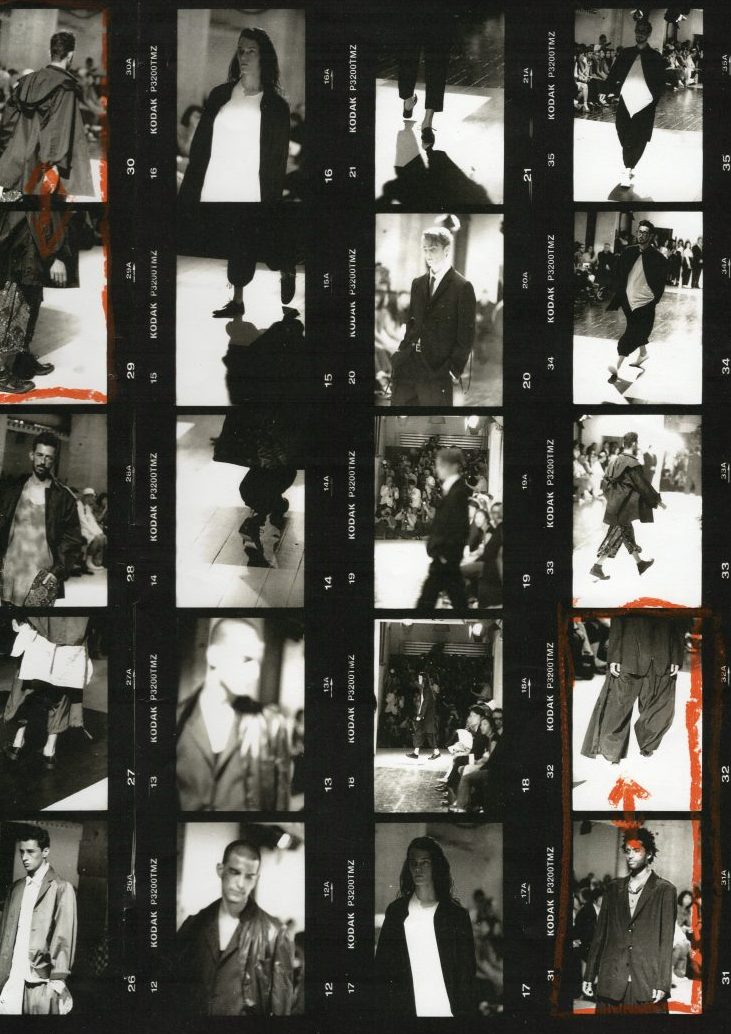

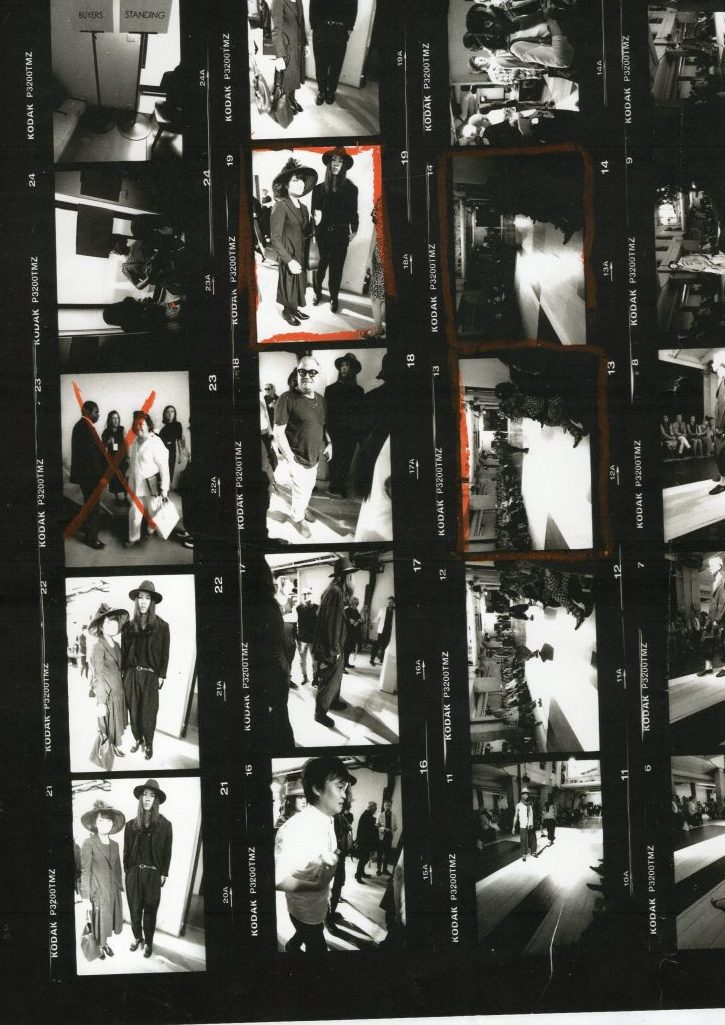

In the interview, Yamamoto talks about his childhood in Japan, punk and protest, cigarettes and alcohol ("the most delicious things in the world"), anti-fashion, and a skirt for Obama. The interview, accompanied by Jerry Berndt's magnificent photographs, appeared in the art magazine *art* in September 2012. I recently rediscovered these images. Jerry captured the essence of Yamamoto. They aren't flattering, glossy shots, but rather existential, honest testimonies in magical black and white. Besides the portrait session, Jerry also photographed Yamamoto at his fashion show and in his studio. Most of these images have never been published. Jerry died unexpectedly a year after the interview, and the photos, along with proofs and contact sheets, lay forgotten in a photo box for years. Now they've resurfaced, along with my interview, which still sounds quite sharp.

UTE THON: Mr. Yamamoto, last night's fashion show was fun. Your new menswear collection is surprisingly colorful and playful. However, there was one disconcerting aspect: all the models had makeup to look like abrasions and bruised eyes. What was your intention with that?

YOHJI YAMAMOTO: It should look like boys after a fight. I don't know if something like that was common in France back then. In Japan, anyway, we had a lot of street fights when I was young. You know, for young people, especially boys, fighting is quite natural. When I was young, I was constantly involved in street fights; sometimes the police even came and broke up the fight, but they always let us go. Nowadays, if something like that happens, the police immediately issue a ticket and send the kids to court. That's called 'compliance,' acting according to the rules. There are too many compliance rules in our society. If I smoke a cigarette on the street in Japan, I have to pay a fine.

Are your clothing designs therefore to be understood as a protest against too many rules and regulations?

At least I think it's a nice idea.

Yesterday's show marked your 31st year in Paris and your 40th anniversary as a fashion designer. Do you still get nervous before fashion shows?

There's a slight difference between the men's and women's collections. I'm not really nervous before men's fashion shows. Not because designing for men is easier. On the contrary. It's actually more difficult because you quickly reach your limits with menswear. There's only a limited number of garments: jacket, trousers, shirt. It's hard to experiment with that. With women's clothing, on the other hand, the creative freedom is limitless.

With your designs, you have repeatedly broken fashion conventions. You've shown slender women in oversized uniform jackets and had men wear wide, flowing skirts. Is this your personal revolt against the fashion establishment or an act of female liberation?

It has nothing to do with conventions. I simply chose to work on a side path in the fashion industry. There's the main fashion street, but that never interested me. I've always worked against the grain. I design anti-fashion.

Anti-fashion? What exactly do you mean by that?

If designing fashion can be called art, then perhaps I am an artist. And I believe an artist's mission should be to do something against conventional thinking, against ordinary worries. Only by resisting the rules of society can we find a new way of living. Swimming with the mainstream might be comfortable, but it wasn't for me. Because even as a child, when I was five or six years old, I harbored strong doubts about life. I was angry at the conformity of society and the role of family.

How would you define your role? Do you see yourself as an artist?

I wouldn't call myself an artist. Most people call me a fashion designer, but I see myself as a tailor, a dressmaker, a craftsman, not a designer.

Nevertheless, there are many people who admire you for your artistic talents. Your designs have been compared to sculptures and deconstructivist art. They have been exhibited in art museums. Does that bother you?

Yes, sometimes. Since the end of the 19th century, there has been a great deal of uncertainty in the visual arts. The question arose: Is it even possible to produce pure paintings and sculptures for the 20th century anymore? Later, there were strong influences from America, Andy Warhol and Pop Art. I think Pop Art and fashion are closely related. In earlier times, artists were commissioned by the most powerful rulers, emperors and kings, to produce masterful paintings and sculptures. That was perfectly acceptable at the time. But today, these power structures no longer exist. Every individual has to make an effort and find ways to awaken new emotions and change people's perceptions. This challenge has become the role of the artist.

Are there any particular artists or works of art that have especially influenced you?

Not really. Sometimes I'm inspired by photographs, for example by Man Ray. He's fantastic. For me, very well-made photographs are more powerful than any painting. (He reaches into his jacket pocket and pulls out a pack of cigarettes.) Do you mind if I smoke?

Not at all. Please smoke.

(Lights a cigarette and inhales with relish) Cigarettes and alcohol are the most delicious things in the whole world.

But not necessarily the healthiest. They foster creativity—or at least we believe they do. I'd like to learn more about your creative method. Where do you begin?

It all starts with the fabric. And with a certain appreciation for imperfection. I've always liked asymmetries, both in design and in people. Simply put, I like people's flaws and think many of their attractive qualities stem from their imperfections. Uniformity in form and character drives me crazy.

Cigarettes and alcohol are the most delicious things in the whole world.

What is the fundamental difference in designing women's and men's clothing?

Because I'm a man myself, I understand a man's skin. I can easily grasp what kind of fabric and what cut might be comfortable. When I design menswear, it feels like I'm making it for my friends. These aren't things for conservative bankers or government officials; they're things for free people, artists, musicians, the homeless. For me, they're all on the same level. With women's clothing, it's different. I'm not a woman; I don't have her skin or her feelings. Women are always mysterious; every time, I wait for that special mix of excitement and conflict between the woman's body and my clothing. I have to fight for that every single time—for the moment when the clothes and the model's body first meet. That, for me, is the magical moment.

In Germany there's a saying, "Clothes make the man!", which suggests that a tailor has a lot of power. Would you agree?

I believe that clothes can change people. When a young girl wants to buy an outfit from me for the first time, I tell her: You have to change your whole lifestyle for that. If you lead a completely normal, ordinary life, you can't wear my clothes. You have to become a free person—or a misunderstood person. If you wear my clothes, you can't become the CEO of a big company.

If the President of the United States of America wore my skirt, there would be no more wars.

Why not? Don't you think attitudes have changed in the executive suites as well? Wouldn't it be great if Barack Obama wore one of your skirts in the Oval Office?

If that happened, the world would be a completely different place. If the President of the United States of America wore my skirt, there would be no more wars.

Then you should send him one as soon as possible…

(laughs) Yes, maybe I should.

It has often been written that your clothes say a lot about your Japanese heritage and reflect a particular Asian, Zen-like philosophy. Especially at the beginning of your career, you always rejected this and didn't want to be pigeonholed. What is your current stance on the Japanese influence on your work?

I was born in Japan and have Japanese DNA. Therefore, I don't need to act particularly Japanese when I use international techniques. People see the Japanese spirit in my designs, something they have to invent themselves. I don't have to invent anything; I do it naturally because Japan is within me.

It would be far too simplistic to reduce your clothes solely to Japanese influence. I think that your early designs, especially those made from raw fabrics with unfinished seams and hems, reflect the rebellious spirit of the 70s and early 80s, such as the London punk rock scene. Is there a connection there?

I generally like punk fashion. But as a movement, it didn't go any further. Punk isn't a philosophy; it's the outcry of youth—young people screaming like babies. Eventually, we grow up, but we keep the spirit of youth in our hearts. That's important because it's a very pure feeling.

What feeling do you carry in your heart?

Anger! Anger that I've grown up. It's a huge paradox. Lately, I've even started to really hate myself for getting old.

If your collections reflect your mood, it's actually quite dark. Your favorite color is black, although in recent years you've occasionally mixed in a bit of red or orange. How do you use color?

It all started with the idea that modern metropolises like London, Paris, New York, or Tokyo are already teeming with so many different types of people. If they all wear different, garish clothes, it makes the city dirty and ugly. I firmly believe that people in modern metropolises should wear uniforms. And if you were to ask me, I would be more than happy to design them. In a democracy, of course, the freedom to choose one's outfit is one of the freedoms, and that's wonderful. But with this freedom comes a great responsibility. When I started designing clothes, I didn't want to confuse people's eyes and worked only with monochromatic colors: navy blue, black, beige. Now I also use brighter colors. This is my statement against the prevailing opinion that Yohji can only wear black.

I firmly believe that people in modern cities should wear uniforms. And if I were asked, I would be more than happy to design them.

The Holon Design Museum is holding a retrospective of your work. In the past, you have often expressed doubts about exhibiting clothes in a museum. Have you changed your mind?

Exhibiting in a museum is still a challenge for me. But I want to see what feelings it evokes. A few years ago, I had a show at the Fashion Museum in Antwerp. Back then, we decided that visitors could not only look at the clothes but also try them on. I liked that concept. In Holon, people have the opportunity to touch my pieces. That's very important because, for fashion creations, touch is the key. There are many art forms—painting, music, or theater—where we only use our eyes, ears, and noses. But in fashion, the sense of touch is essential.

You use only fabrics from Japan. What's so special about them?

It's about craftsmanship unlike anything else in the world. At my request, the weavers start from scratch with the selection of yarns, creating a completely new fabric. Otherwise, the process of cutting and draping wouldn't be interesting, because designing is about constantly inventing something new. I don't want to be the king of style, always making the same designs. That's so boring. I want change every time, a new challenge, even if that's a huge mistake commercially. But for me, the challenge is what matters most.

You also designed theatre costumes, including one for "Tristan und Isolde" at the Bayreuth Wagner Festival in 1993. Later you collaborated with Pina Bausch…

I also designed costumes for films by the Japanese director Kitano and Wim Wenders, but never for Pina Bausch. That's a rumor. She asked me to create something for the opera house in Wuppertal to celebrate the 25th anniversary of her company. So I did an improvised performance on stage.

I've heard that you occasionally perform on stage, playing guitar and harmonica and singing the blues. Do you still do that?

Yes, that's my hobby. I like Black music. It's the only culture from the United States that interests me. It's a culture that comes from oppression, and I feel connected to that.

Yohji Yamamoto is one of the world's most influential fashion designers. Born in Tokyo in 1943, he grew up as a half-orphan—his father had been killed in the war—in war-torn Japan. His mother supported the family as a seamstress. He was interested in her craft but was initially supposed to study law. Later, he transferred to the prestigious Bunka fashion school in Tokyo, where he graduated with top honors. In the early 1970s, he launched his first designs under the label "Y's," characterized by minimalist forms and sophisticated tailoring techniques in his favorite color, black. In 1981, together with his then-partner Rei Kawakubo of the Japanese avant-garde label Comme des Garçons, he presented his first womenswear collection at the ready-to-wear shows in Paris. The asymmetrical, seemingly unfinished garments sparked both enthusiasm and incomprehension in the fashion world. While the hottest fashion designers sent their models strutting down the runway in high heels, tight skirts, and shoulder pads, Yamamoto's women wore wide-legged trousers, men's shirts, and flat shoes. Within a short time, his clothes achieved cult status and became the preferred uniform of artists and intellectuals, including Wim Wenders, who paid tribute to the Japanese avant-garde designer in 1990 with his film "Notes on Clothes and Cities." Yamamoto's designs are often interpreted as a protest against mainstream Western fashion aesthetics. His influence on younger designers like Junya Watanabe, Martin Margiela, and Marc Jacobs is undeniable. Moreover, he is one of the longest-lasting designers in the ephemeral fashion industry. Yamamoto's empire comprises around 300 stores worldwide with an estimated annual revenue of $100 million.

All photos: Jerry Berndt, Paris 2012: Copyright: Jerry Berndt Estate